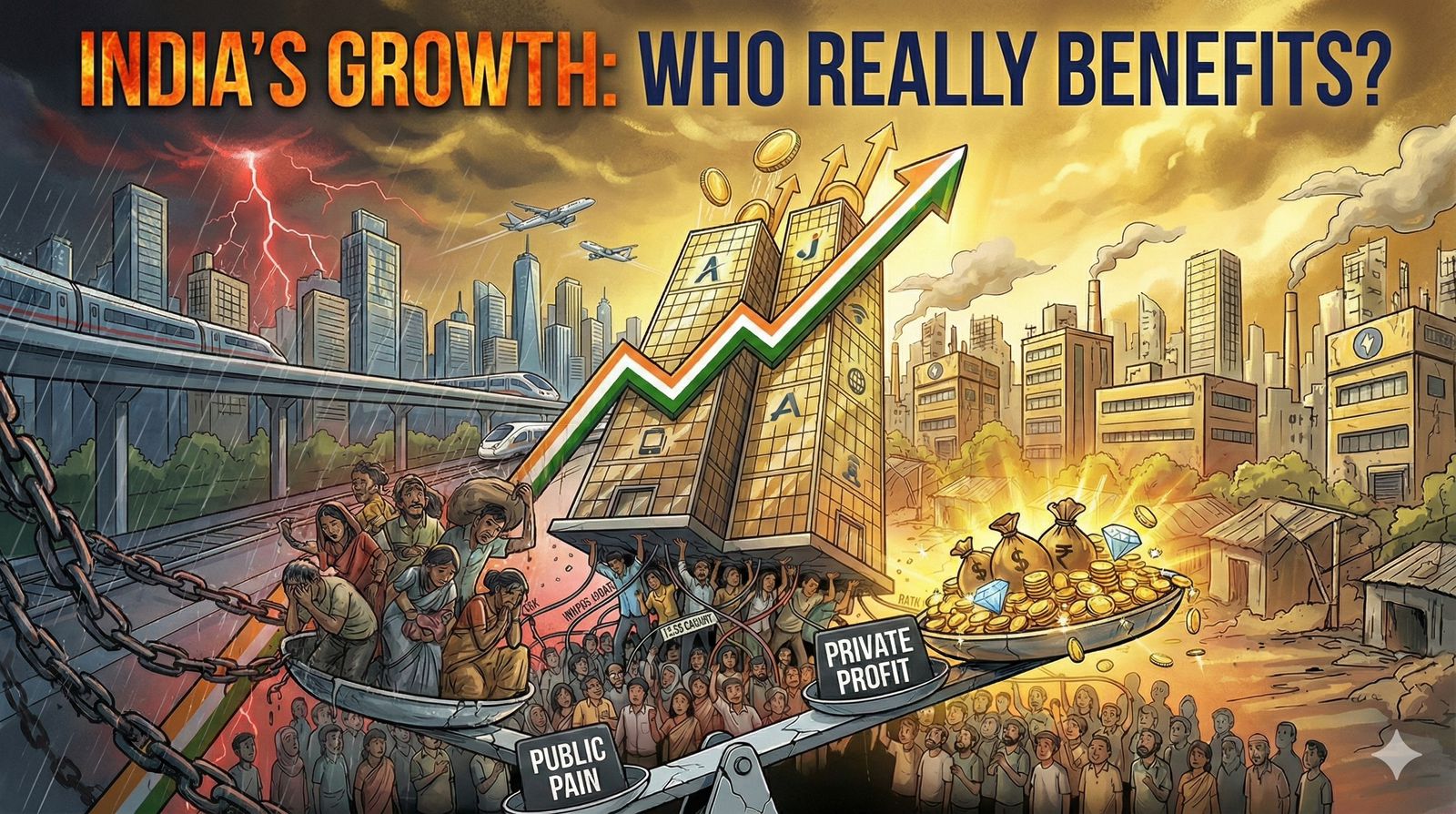

India’s growth story is sold to us in big numbers. Fastest-growing major economy. More flights in the sky. The world’s cheapest data. New UPI records every month. It all sounds impressive, and much of it is true. But there is another side to this story. As the market grows, it is also narrowing. Not in terms of profits, but in terms of who controls them.

In sector after sector, the pattern is the same. Two or three companies hold most of the market. In textbooks, this is called a duopoly or an oligopoly. In everyday life, it means something very simple: you and I have fewer real choices, and a few big companies have far more power than before.

Domestic aviation is the clearest example. IndiGo is the dominant carrier. Air India is growing again after its merger and rebranding. Together, they carry most of India’s air passengers. When everything works, this looks efficient: one ticket, one app, flights to almost every major city. But when something breaks, the whole country feels it. Flights are cancelled or delayed for hours, fares shoot up, and people sleep on airport floors. A problem in one company’s operations becomes a national inconvenience. Profits remain private, but the risk and the pain are shared by the public. That is what “too big to fail” looks like in practice.

Telecom has followed a similar script. A few years ago, India had many mobile operators. Today, the market is effectively dominated by Jio and Airtel. One more private player is struggling, and the public operator is weak. Ultra-cheap data and free calls looked like a gift at first, but smaller companies could not survive that price war. Now that the dust has settled, tariffs are rising again. On paper, consumers can switch between networks. In reality, both big players know that it is hard for most people to walk away.

The same pattern appears at our physical gateways. Ports and airports are not just buildings. They are the doors through which people and goods move in and out of the country. A small number of private groups now run a large share of this network. They handle big chunks of cargo and operate several key airports. If one of these groups faces serious trouble, it is not only their profit-and-loss sheet that shakes. Trade, exports, jobs and prices across the country can all feel the impact. What is sold as “efficiency” can easily turn into dependence.

On the digital side, the picture is quieter but sharper. UPI is a genuine public success, a digital rail built in the public interest. Yet the apps that sit on top of it are mostly private. PhonePe, Google Pay, Paytm and a few others handle most of the traffic. In theory, the system is open to many players. In practice, our daily money habits pass through a handful of apps that control the interface and hold the data. We know very little about how their algorithms work or whose interests those algorithms really serve.

E-commerce tells the same story. A few large platforms dominate what we see and buy. Small sellers depend on them for visibility and sales. Customers increasingly search inside these platforms, not on the open web. We are told that we live in an age of “infinite choice”. But the shelf is designed by a handful of companies, and their code decides what appears on the first page and what remains hidden on the twentieth.

Defenders of this model say that India needs scale. They are not wrong. Big projects and global competition do require strong companies and deep pockets. The question, however, is not simply “big or small”. The real questions are: who sets the rules, who has the power to say no, and who can stand up to a large corporate when it crosses a line?

When a few corporations dominate infrastructure, media, data and finance at the same time, their influence over policy naturally grows. They give large donations. They buy a lot of advertising. They own or fund media houses. They can shape which issues become national debates and which ones never quite make it to prime time. Slowly and quietly, the centre of decision-making can shift away from citizens and towards boardrooms.

We have seen versions of this story in other countries and at other times. The lesson is simple. Unchecked concentration of economic power creates fragile systems, not only in markets but also in society and politics. When too much depends on too few, everything looks fine until it suddenly does not.

Breaking this pattern does not mean being “anti-business”. India needs investment, innovation and strong firms. But it also needs a state that can regulate powerful players, and citizens who can question them. That requires at least three changes.

First, we need a serious competition-law mindset. Regulators cannot look only at prices. They also need to ask who controls data, networks and platforms. Mergers that leave only two or three major players in a sector should face real scrutiny, not be treated as routine paperwork.

Second, deals in strategic sectors must be far more transparent. Ports, airports, logistics corridors and natural resources are not just assets to be sold. They are part of the country’s long-term sovereignty. There should be clear limits on how much one group can own or operate, and safeguards to ensure diverse ownership.

Third, we need strong public or cooperative options wherever they make sense. UPI itself is proof that a public rail can keep an entire ecosystem more honest. In some sectors, a real non-corporate alternative is the only way to preserve meaningful choice.

In the end, this debate is not only about economics. It is about power and about who the economy is meant to serve. Market freedom is important, but it cannot sit above citizens’ freedom. Real development means more than a rising GDP line. It means spreading opportunity, keeping choices open and sharing risk. If we forget that, we may build a high-growth economy and one day find that our democracy has quietly grown much smaller than we thought.